Compact Hardcovers, Confessions, and the Curious Practice of Embossing Names on Bible Covers

It's time to answer more questions from readers. Some of these go way back, others are recent. If you have questions, do get in touch and I will answer them as I'm able. COMPACT HARDCOVERS Max Vitullo can’t find what he’s looking for: “I am looking for a hardcover, single column, black letter, compact Bible. Do you happen to know if this exists anywhere?”

This would have been an easy question to answer if not for the final detail: compact. If you’re looking for a single-column black letter hardcover, look no further than the ESV Reader’s Bible (reviewed here). Does it qualify as compact? Not so much. While the Reader’s Bible isn’t exactly hefty, describing the thing as compact would be a stretch: it measures 8” x 5.5” and runs about 1.5” inches thick. (The Clarion is slightly trimmer, but not available in hardcover.)

Even so, I think the Reader’s Bible is as close as you’re going to get for now. Setting the text in two columns allows the use of much smaller type, which is why every truly compact edition of the whole Bible I can think of is double-columned. A compact single column would be wonderful. Until someone takes the risk, though, the Reader’s Bible is your best bet.

CONFESSIONS Justin Bond wants a Bible with the London Baptist Confession of 1689 in the back. That’s not all he wants, though. I’ll let him explain: “I am on the hunt for a good ESV bible that includes the London Baptist Confession of faith. Do you know of any options available? I know that there is the Schuyler ESV that includes the creeds and confessions (LBCF) but I am not a fan of having ‘Holy Bible’ printed on the front. Is there an option to leave the cover blank?”

I wish I could refer you to a half dozen other editions, but to be honest, the fact that there’s even one is quite a coup. After floating this idea with publishers for years, Schuyler was the only one to take an interest. I’m grateful they did. The Schuyler ESV with Confessions (reviewed here) is what you should get.

As far as I know, Schuyler doesn’t have plans to reprint the edition with an unembossed cover. Presumably they would if there was sufficient demand. (You can always ask.) That leaves you with two options. Both are expensive, but one is more expensive than the other.

The really expensive option is to buy the Schuyler ESV with Confessions and have it rebound to your specifications. The expensive option is to buy the Schuyler ESV with Confessions and don’t have it rebound. Instead, reflect on the fact that, as the theologian Mick Jagger once said, you can’t always get what you want. Getting this close isn’t half bad.

THE CURIOUS PRACTICE OF EMBOSSING NAMES ON BIBLE COVERS Steve Allen asks: “What do you think about embossing names on the front an expensive gift bible such as a Schuyler. Great idea? Or just stick with writing something on the presentation page?”

This will probably make me as popular with the all-powerful embossing industry as the Apostle Paul was in Ephesus, but my advice is to skip the emboss and make use of the presentation page. I’ve never seen the point of embossing names on Bible covers—though it’s a curious practice and I’d love to know how far back it goes and how it got started.

I’m pretty sure every Bible in my possession before the age of twenty had my name stamped in the lower right-hand corner of the cover. The one pictured below in a Nelson KJV in bonded leather given to me after my high school graduation. There should be a J. at the beginning—perhaps that omission is what turned me against the practice.

Maybe I’d feel differently if the embossing where done in a more attractive, non-scripty typeface.

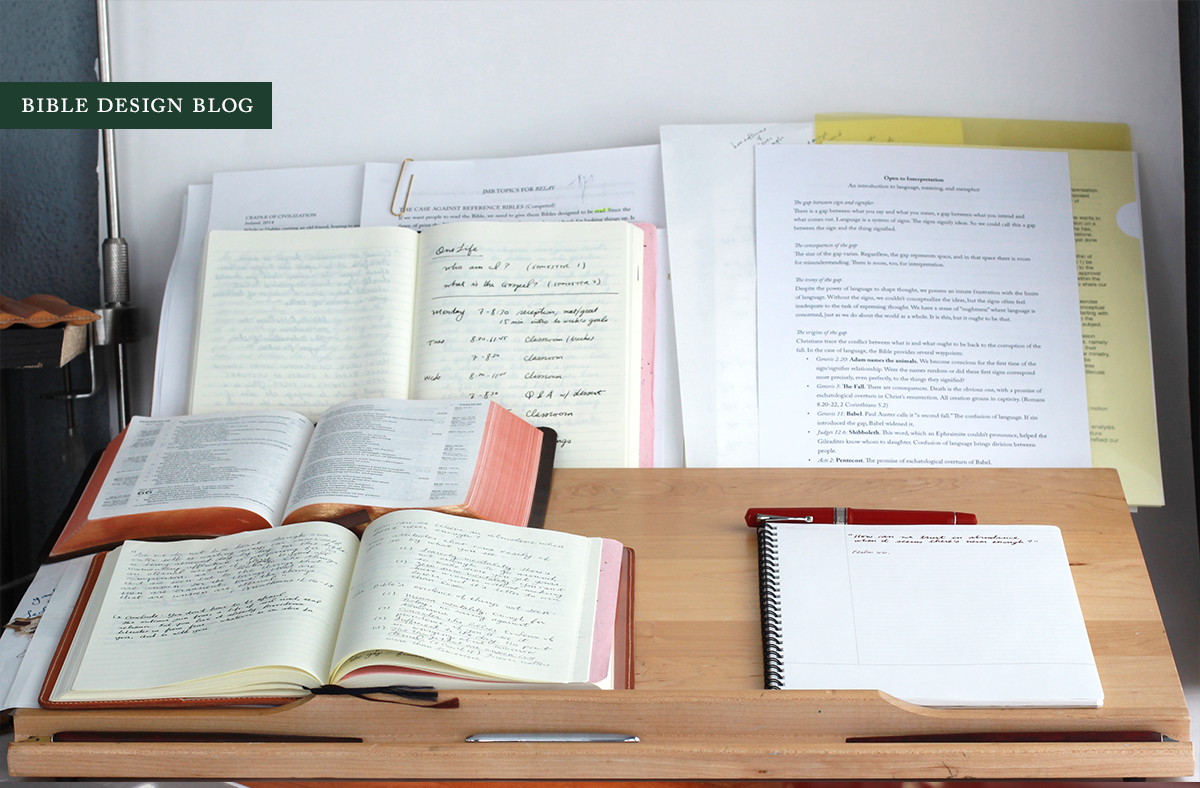

MORE ON STANDING DESKS Following up on last week's question about standing desks, I figured it would be helpful to illustrate why I like them so much. The killer combination, for me, is having a slanted work surface at just the right height for writing by hand. I snapped this photo while working on a sermon I gave yesterday. You can see my current journal open (lower left) to display notes I'd made while thinking through the text, and a Cambridge Clarion just above for reference. On the right is a spiral notebook I used for developing a clean copy of the outline, and propped in back are a number of random things, some relevant to the work and others not.

As I worked, I wandered away for awhile, then returned, pacing the room as I ordered the flow of words in my mind. That ability to leave and return throughout the process is one of the advantages I've found. When I sit to work, the drive to finish seems to take over -- which is a virtue when there's a deadline to meet, but that race to the finish doesn't lend itself as easily to a more meditative task (at least not for me).

J. Mark Bertrand is a novelist and pastor whose writing on Bible design has helped spark a publishing revolution. Mark is the author of Rethinking Worldview: Learning to Think, Live, and Speak in This World (Crossway, 2007), as well as the novels Back on Murder, Pattern of Wounds, and Nothing to Hide—described as a “series worth getting attached to” (Christianity Today) by “a major crime fiction talent” (Weekly Standard) in the vein of Michael Connelly, Ian Rankin, and Henning Mankell.

Mark has a BA in English Literature from Union University, an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Houston, and an M.Div. from Heidelberg Theological Seminary. Through his influential Bible Design Blog, Mark has championed a new generation of readable Bibles. He is a founding member of the steering committee of the Society of Bible Craftsmanship, and chairs the Society’s Award Committee. His work was featured in the November 2021 issue of FaithLife’s Bible Study Magazine.

Mark also serves on the board of Worldview Academy, where he has been a member of the faculty of theology since 2003. Since 2017, he has been an ordained teaching elder in the Presbyterian Church in America. He and his wife Laurie life in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.